A couple years ago I bought a cheap "large patch knife," made in Pakistan. While I'm not aware of any historical knives that it resembles, some of its features make it look like a 19th-century Bowie knife. It really lacked only a guard and a more appropriate scabbard. So last year I set about turning it into one, and I've just gotten around to finishing the job in the last few days.

It may seem at first glance more sensible to start with a bare blade of the same pattern; however, I have reason to believe that these blades when sold unfinished are not always hardened, whereas the knife I bought was well-reviewed, with no complaints about its edge retention. That and some shopping around indicated that I could get a finished knife cheaper.

What I feel was a mistake was not saving the scales, which were some kind of probably tropical hardwood and, I suspect, tougher than the wood I replaced them with. Keeping them would've made refinishing much faster. They weren't glued on; actually I don't think there was anything really holding them in place except the pins, which were ground down to make the fit flush. Unfortunately I wrecked them in the process of prying them off.

19th-century Bowies with straight backs and upswept edges seem to be very rare, so the first modification I made after removing the scales was to grind on a clip point.

The finger guard is an inexpensive sand casting from Crazy Crow. The first step was filing out its slot so that it would fit over the pommel swell of the tang. I next had to figure out a way of fixing the guard. A scale-tang knife can have a fixed guard pinned between the shoulders and scales, but this one had only one shoulder, which was sloped, and the tang was wider at the butt end, so even if the guard couldn't slide up and down, it would be able to slide side-to-side.

Killgar at BladeForums suggested a solution: pinning some pieces of brass bar in place and soldering the guard to them. I didn't entirely understand the idea, and wound up making the guard's slot wider to fit over the brass strips, which makes it a bit uglier to look at.

The scales are cherry, also from Crazy Crow, with inlets sanded in so they fit over the brass strips. Another way of doing this that is only just occurring to me would have been to make the brass in the form of full-profile liners, which would obviate the need for inletting the wood scales.

The cherry wasn't as dark as I'd have liked, so I stained it with Minwax mahogany mixed with just a bit of Minwax ebony. I then applied boiled linseed oil and finished with Tru-Oil. Pinning the scales left them dented and dingy, so I sanded most of the damage out, re-stained and re-finished.

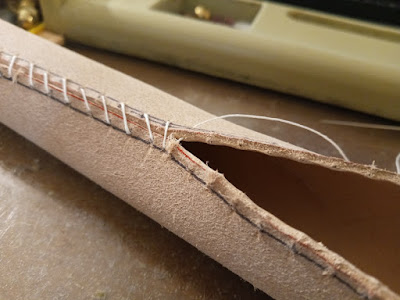

The scabbard is lightweight veg-tan. Sheffield scabbards seem to have normally been black or red. Since I have no red leather dye left and I've never been able to satisfactorily neutralize vinegaroon, I used Fiebings pro black, sealed with Resolene and gave it a light oiling by filling it up with olive oil and immediately pouring out the excess. The fittings are brass, fitted in the usual way, with a fabricated and soldered frog button and a stapled throat (stapling was tricky this time because the sheath fits very tightly around the blade's ricasso).

Here it is next to a non-modified example. The grip as I made it has a very slight overhang around much of the tang. The non-modified one must have been flush when it was made, but at the moment the scales seem to have shrunken, most likely due to changes in humidity, and some of the sharp edge of the tang is exposed. In this way the new grip is more comfortable.

Less fortunately, the added guard leaves less room to grip. It just barely fits in my hand (glove size medium); for anyone with larger hands it just wouldn't work.

While the frog button allows the scabbard to be worn on the belt, the small size makes it just as appropriate as a boot knife or even in a large overcoat pocket. However, due to the tight fit in the ricasso area, it's not currently possible to push the scabbard off with the thumb the way I normally would prefer to do when drawing such a knife from a coat pocket. The solution I'm currently attempting is to dampen the sheath and shove a smoothed 1 x 1/8-inch brass bar into the top to stretch the leather.