Addendum

"That's not quite what happened," Algernon began.

Monday, December 22, 2025

You can memorize this one

1 cup powdered sugar

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

2 cups flour

6 ounces mini chocolate chips

1/2 cup finely chopped nuts (optional)

Makes six to seven dozen

1. Preheat oven to 325 degrees Fahrenheit.

2. Mix butter, sugar and vanilla in a mixing bowl.

3. Stir in flour.

4. Mix in chocolate chips and nuts.

5. Roll and flatten one-inch balls of dough, place them two inches apart on baking sheets. Or cut or mold like shortbread.

6. Bake 20-25 minutes.

Thursday, September 4, 2025

A smallsword from Armlann Gàidhealach

They strongly resemble the so-called pillow or scarf swords of the previous century, with very short blades (as little as 24 inches) and no knucklebows or finger rings. They were made with a pattern of lightweight rapier blade called a smalle Doljch, which O'Shaughnessy and MacNeill imported from Solingen, where they were made by the small workshop of Hoffmann Schwieets. In Edinburgh, they were shortened from the point and tang end to eliminate the long ricasso and produce a delicate little blade.

I am currently saving up for a standard-pattern "wee claybeg," but I wanted to first get ahold of this absolutely unique variant. It was created in January 1746 along with a dagger and miniature targe for Andrew Aldridge of Beinn Sgleatach, who, however, did not accept or pay for them. This is a good thing, since I wouldn't want to own anything he had owned, for reasons that will become clear.

The blade is a kort Doljch, a shortened version of Hoffmann's earlier heavy rapier pattern, which was also used in pillow swords. O'Shaughnessy seems to have produced this sword as a more battle-worthy version of the wee claybeg, as not only the blade but also the fittings are more massive and sturdier. Hawkins tells me that the matching targe is only 11-1/2 inches wide, which I would normally consider too small for a strapped shield unless the wielder's forearm with closed fist is itself less than 11-1/2 inches from elbow to knuckles. I've usually read that targes were at least 16 inches wide at the smallest; the last one I obtained is this size and feels barely wide enough for me. A strapped shield smaller than that not only provides less protection in general, but, if shorter than the wielder's forearm, would run the risk of allowing blows that strike between the 6 to 8 or 10 to 12 o'clock positions to skate around and strike the elbow or upper arm, and give no protection at all to a sideways blow in line with the elbow. That's why usually the only shields this small are center-gripped, like bucklers or dhals. A tiny strapped shield and short sword only make sense in the hands of someone who was fast enough to get close to an opponent while avoiding their attacks or receiving them in such a way as to avoid being injured.

This actually appears to have been the case. O'Shaughnessy described Aldridge to the Hawkinses as "five fit lang yet unco bonnie an' byous swith." (O'Shaughnessy seems to have been a secret admirer of his, perhaps because she was very short as well.) This letter seems to have been the source of James McKay's description of him in "The children of Ailpean" as "Five feet tall and swift of foot." A popular joke about Aldridge was that his mother, whose identity isn't known, was of the Unseelie. McKay himself was present at Culloden as a lieutenant under Colonel Cornelius Ridge, Aldridge's English cousin. Near the end of the battle Aldridge, who had been saving his last bullet for Ridge, shot at him but only hit his horse. The two then charged at each other with swords, with Ridge very nearly losing the duel due to Aldridge's terrifying speed. Aldridge was only defeated when half a dozen soldiers under Lieutenant Paul Hurt (later a Captain and later still husband of Sylvia Hawkins) surrounded and fired on him all at once. An infuriated Ridge then took McKay's pistol and finished off his injured cousin. In describing the incident to Ridge's nephew Corporal Robert Ridge (who joined the regiment after Cornelius' "suicide" in 1755) McKay claimed that he saw two shadowy little phantoms appear above Aldridge's body, one a woman with long hair who dragged the other away by the hand, and what he described as the laughter of many thin voices like tin whistles heard far away. It was the terror of this experience, as much as the moral repugnance of the Duke's orders, that made McKay and Hurt refuse to participate in the execution of wounded Jacobites after the battle. For this they were both dismissed, though their commissions were reinstated several months later.

It was also this experience that inspired "The children of Ailpean," which described how Ailpean Aldridge and all his descendants were cursed due to a fight between him and the Unseelie princess Cornelia. It is a matter of historical record that all his descendants on both sides of the border died before the age of 50 and violently. The sole possible exception is Andrew's father Geoffrey, who dropped dead shortly after Culloden, and even this McKay attributed to being slain by fairy-shot by Cornelia herself, whom his poem casts as the mother of Andrew and the phantom who dragged Andrew's soul away to join the Unseelie. Cornelius Ridge's "suicide" was rumored to have been murder at the hands of his lieutenant colonel and successor, Sir Laurence Pemberton. Even Robert Ridge would die in the French and Indian War at the age of 25 when his company was ambushed in the woods west of Cayuga Lake. What became of Andrew's possessions is unknown, but "The children of Ailpean" ends with O'Shaughnessy burning Andrew's body, sword and shield on a pyre and burying the remains in an old mound in Beinn Sgleatach to break the curse.

So how do I have these? Armlann Gàidhealach actually made two swords, and a number of other weapons, for Aldridge. These were listed in invoices as "1 short claybeg or 1 wee claybeg," "1 short claymore w. half-basket" "1 wee targaid w. strap," "1 wee targaid w. nae strap," "1 wee dirk w. chip knife," "1 wee dagger" and "2 belts." (What O'Shaughnessy calls a "chip" knife is what we'd call a by-knife, a miniature version of a general-purpose belt knife with a curved cutting edge, carried in a side pocket of a larger blade's sheath or scabbard. Don't ask me where she got the word "chip" from. Although "chib" is a modern Scottish word related to "shiv," these are borrowings from Romani and not attested before the 20th century, so they're unlikely to be related to O'Shaughnessy's "chip." There's also a modern style called a chip knife or chip carving knife, but it has a specialized woodcarving blade with a straight cutting edge and curved spine, so, again, it's probably not related.) The ones he actually bought were the claymore, the targe with no strap, the dirk and its by-knife, and one of the belts. I can only guess what the claymore looked like, but I suspect the targe without a strap was identical to the remaining one except with a central, probably rigid grip, and that he chose it in order to give himself greater freedom to use it like a center-gripped buckler, eliminating the aforementioned problems with a small strapped shield. The short claybeg with its matching belt, small targe with strap and small dagger comprise the part of the assemblage that he didn't buy. I have them reserved but they won't join my collection until I can pay for them. The dirk, on the other hand, was a unique piece that I'm working on reproducing from drawings; you'll see it shortly.

The blade for this sword was custom made for me by Darkwood Armory. For process pics and other information on this project, click here.

Tuesday, June 10, 2025

German hunting trousse, part XII and the unexpected problem

To try to keep the facing from crushing the side pockets, I inserted the knife and fork. To keep the facing smooth above the pockets and prevent the protruding rivet heads from making marks in the damp leather, I placed some small brass plates. The space between the top of the scabbard and top of the side pockets is almost exactly two inches.

To get the facing to mold as closely to the core as possible, I used most of a bag of binder clips. These somehow seem to have stained the back with little black spots, possibly from exposed steel on the edges reacting with the veg-tan (similar to vinegaroon).

Once the facing was dry, I trimmed to down to the straightest, closest edges I could manage using a combination of an xActo chisel point and scissors.

|

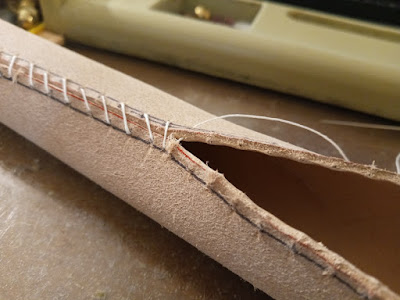

My plan was to loosely stitch the outer layer, soak it, insert the core and tighten the stitches one by one.

It proceeded according to plan except that I could only manage a single whipstitch with the length of linen thread I'd cut. The outer layer shrank nicely against the core. The problem of the facing above the pockets being a bit too large remains, but while unsightly, it's not too bad for me to overlook on a first attempt.

The use of two brass plates had caused a visible line across the top of the facing during the initial wet molding, so this time I added a single two-inch plate. This did seem to help.Unfortunately, a new problem came up at the end: It seems that some of the hide glue I added to fix the facing in place either soaked through the wet leather or got out at the seams and onto the facing. The glue appears to have interfered with the absorption of the spirit dye, so that repeated brushings of dye failed to get rid of the patchy appearance. Whether this problem can be solved at this point and how, I'm not sure.

Monday, May 26, 2025

German hunting trousse, part XI

The messer scabbard is two layers of fairly thin veg-tan. The inner layer is unstitched, while the outer layer has a flat Z-shaped double whipstitch, unlike the double running stitch I'm used to using that leaves a ridge down the back. The double running stitch is used because it helps keep the stitching away from the blade so that it's harder for the blade's point to catch on the stitching when resheathing. An unstitched layer obviates that risk entirely, but I don't know how they manage to mold the leather to the blade with no stitching holding it in place.

In any event, I felt the need for stitching in the core layer, but also to keep the point at least somewhat away from the stitches. So after measuring and cutting the leather as usual, I trimmed it until it looked like it would just barely wrap around the blade and meet in the middle, then poked stitch holes at an angle so they came out the sides of the cut edges. I stitched with size 40 linen thread and soaked the core with alcohol. On the suggestion of Sword Buyers' Guide poster erichofprovence, I made the core and side pockets rough side out, in order to encourage better adhesion between them and the rough inner side of the facing layer when everything gets glued together. Because it seemed like it was going to be on the loose side, I tried to make sure it dried more snugly by warming it gently over a heater to shrink it, letting it spend plenty of time off the blade, and not wrapping the blade with tape.

The side pocket for the carving knife offered no such easy solution. The 2-3oz. leather is too thin to poke angled holes out the edges. A normal butt stitch would leave the thread exposed to the knife point. A normal side welt would add unwanted bulk, and a double running center seam would create a ridge that would either prevent the pocket from lying flat against the core (if it were on the back) or be visible through the facing (if it were on the front). What I settled on was to mold the pocket so the seam ran along the blade's spine and slightly to one side and down, so that it's not threatened by the blade's point or edge and lies flat against the core.

An interesting thing to note is that the rosin varnish, even after drying in the sun and then ageing for almost two years, still gets sticky whenever alcohol gets on it.

The side pocket for the fork was simpler, and in fact I think it's better not being molded, so the leather doesn't shrink in such a way as to prevent the tines from sliding freely in and out. I did add a very small, thin welt at the tip, but this doesn't seem to prevent the tines from sliding between the stitches if the fork is pushed in too far. I don't think of this as a serious problem.

All this relates to the question of how much metal hardware I'm putting on the scabbard; the Bruegel messer's scabbard, for comparison, has none at all, and although they're from slightly different time periods, I can't help but think of the messer and trousse as forming a matching set. If I made a chape and throat for the cleaver, I'd feel compelled to make one for the messer as well.

Tuesday, April 1, 2025

A 16th-century peasant's sword belt

Last year I bought a secondhand Tod Cutler 16thC Bruegel Messer on myArmoury. After a few modifications, including dyeing the sheath, I set about trying to figure out how to wear it.

The belts in Pieter Bruegel's (the 16th-century Low Country painter whom this sword is named after) paintings are generally narrow (maybe one inch/2.54cm), dark or black, have D-shaped buckles (though spectacle buckles are also occasionally seen) rendered in grey, and no keeper loop. They're apparently worn a bit loose and low for comfort and ease of movement since the belt appears to attach directly to the back of the messer's sheath. The Bruegel messer sheath has a pair of 1-inch slits in the back for this purpose. While possible, there's no indication that the opposite side of the belt is fixed to the clothing or another belt hidden under the outerwear — the parsimonious explanation, supported by Mikko Kuusirati when I raised the subject on myArmoury, is that the friction of the belt against the wearer's clothing is enough to hold it up.

Unfortunately, I worked a little too quickly and in an awkward position on the floor because the work table I usually use is occupied at the moment. This may be why the back wound up a bit sloppy with spots of dye and finish on it.

For the moment, the belt seems to do its job, although I wonder if it would work as well if I weren't wearing a belt with my trousers for it to catch on.

Sunday, October 27, 2024

Sleigh bell belt for White Christmas

Mom's currently costuming a local production of White Christmas at Newtown Arts and tells me there's where a guy puts on a sleigh bell belt made for a horse and dances around for some reason. For ease of use, she asked me to make this like it was just a regular belt, although it's very long because he wears it over one shoulder and across his chest. This is a 1-1/2x48" veg tan strap with a nickel buckle and linen cord, all from Crazy Crow, finished with Fiebings pro dye, Resolene and olive oil (so it won't smell bad like neatsfoot oil). The stitching holding the buckle fold is based on a belt I bought from a thrift store, although I don't know how they hid the knots (I tucked the ends back into the needle and pulled it through the fold). The bells are from Michaels. In order to not chafe the costume, instead of being fixed with curled brass pins the classic way, the bells are tied on through pairs of small holes with some leftover hemp cord that I had hand-waxed with a block of beeswax when making my small bowcase for Plataea 2022.